At this point, some news of the last few weeks will be addressed which, from GES’ point of view, are reason for hope because they contain building blocks of a possible global solution and / or could help to develop a realistic view of the challenges ahead of us.

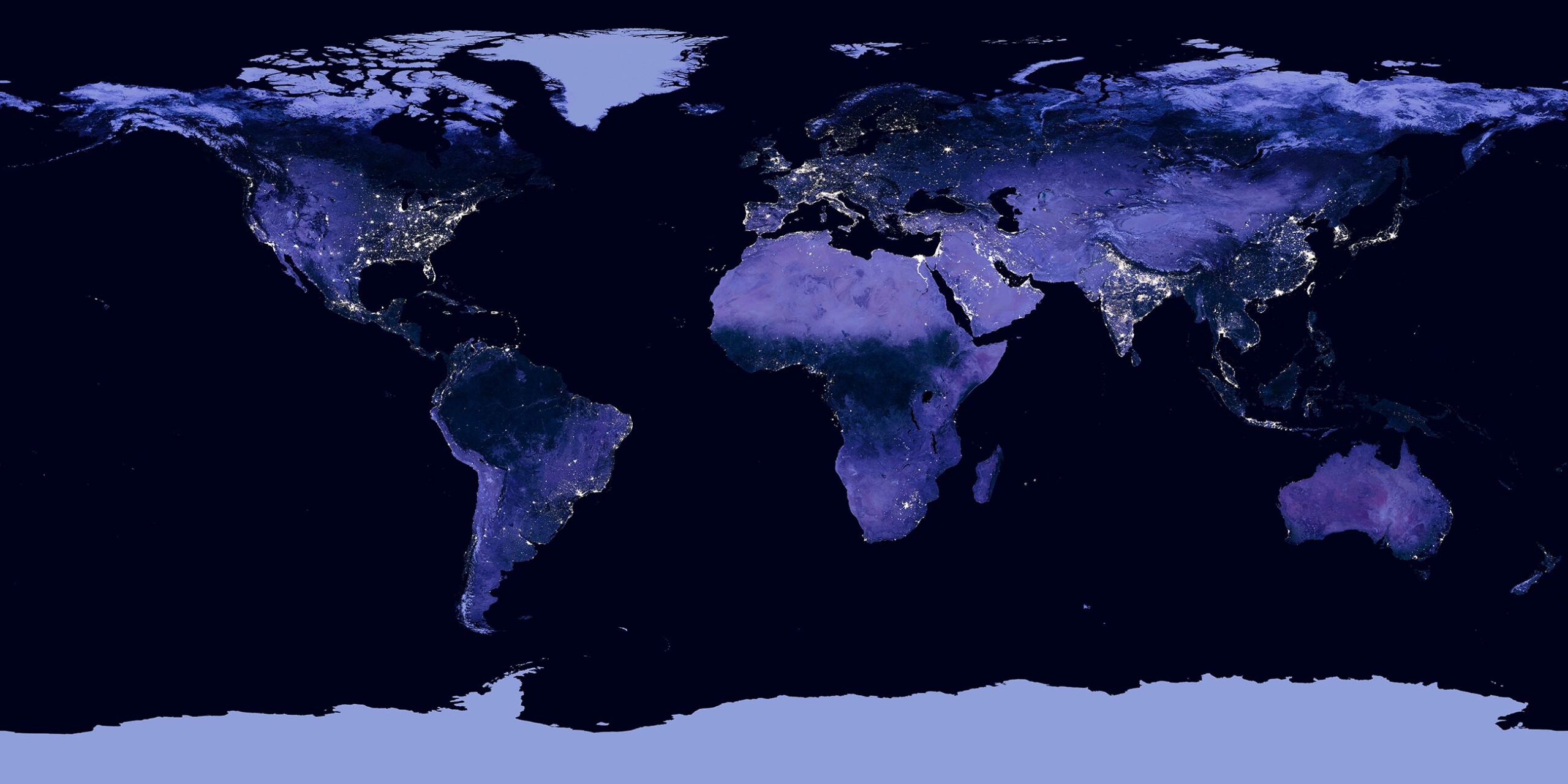

In the final declaration of the first African climate summit in Nairobi, the participating countries call for a global climate tax. The event was meant to highlight Africa’s great potential for renewable energy. So far, however, the capacity on the continent is only 50 gigawatts. Only about two percent of global investments in renewables flow to Africa. Kenyan President William Ruto on the climate tax: “We believe this is one of the ways to provide additional and adequate resources to finance our development.”

Germany imported significantly more electricity in the second quarter of 2023 than in previous years. According to the Federal Statistical Office, net imports amounted to 7.1 billion kilowatt hours. This corresponds almost exactly to the amount of electricity produced by the three German nuclear power plants in the second quarter of last year. At the beginning of this year, all German nuclear power plants were taken off the grid.

In Germany, the construction of the SuedLink power line has officially begun. After years of delays. Because there is no transport capacity available, electricity production from wind turbines in the north often has to be shut down. This shutting down before a grid bottleneck and requesting plants behind it cost 4.2 billion euros in 2022, a quarter of which was spent on compensating renewable power plants for throttling their output. The ten-billion-euro power line is to run 700 kilometres to Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria and make a significant contribution to reducing the problem.

The Greens in Germany are apparently on the verge of a U-turn on carbon capture. At least the blanket rejection is softening. This is shown in the draft of the election manifesto for the European elections in June next year. There is talk, for example, of the cement industry, where CO2 emissions are unavoidable.

Disillusionment at the International Energy Agency (IEA) regarding hydrogen. Despite great potential and many announced projects, there are few investment decisions or construction activities. Currently, only one percent of hydrogen is produced globally with low-emission technologies.

Nevertheless, the IEA believes it is still possible to reach the 1.5 degree target. However, this would require enormous efforts by 2030: a tripling of renewable energies, a doubling of annual energy efficiency and a reduction of methane emissions by three quarters. Experience to date, however, makes this seem very ambitious.

Aircrafts in the EU must be fuelled with 70 percent Sustainable Aviation Fuels by 2050. This has now been decided by the European Parliament. The EU states still have to approve the plan. According to GES research, the target is as ambitious as it is difficult to achieve.

The government of California is suing oil companies for downplaying the risks of fossil fuels for a long time. This has caused billions of dollars in damages. As early as the 1950s, BP, Exxon, Shell, Chevron and Conoco Phillips began to deliberately play down the consequences of burning fossil fuels.

Porsche’s flagship e-fuel project Haru Oni in southern Chile does not yet have its own direct air capture technology. According to Wirtschaftswoche, the plant of the US manufacturer Global Thermostat is still on the factory premises in Colorado. Now engineers from Porsche, Volkswagen and MAN are to develop a suitable DAC system.

The Danish shipping company Maersk has inaugurated its first e-methanol freighter. With a capacity of 2,136 containers, the ship is relatively small and will be used primarily in the Baltic Sea. Maersk has ordered a total of 25 ships that can also run on e-methanol.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) calculates the costs of converting the global merchant fleet to low-CO2 fuels to be high: between 7.5 and 26 billion euros would be spent on ships by 2050, and the infrastructure would cost even more, between 26 and 85 billion euros. Almost 99 per cent of the world’s merchant ships still run on conventional fuels.